by Autumn Ryan, Founder and CEO of The SoRite Company

by Autumn Ryan, Founder and CEO of The SoRite Company

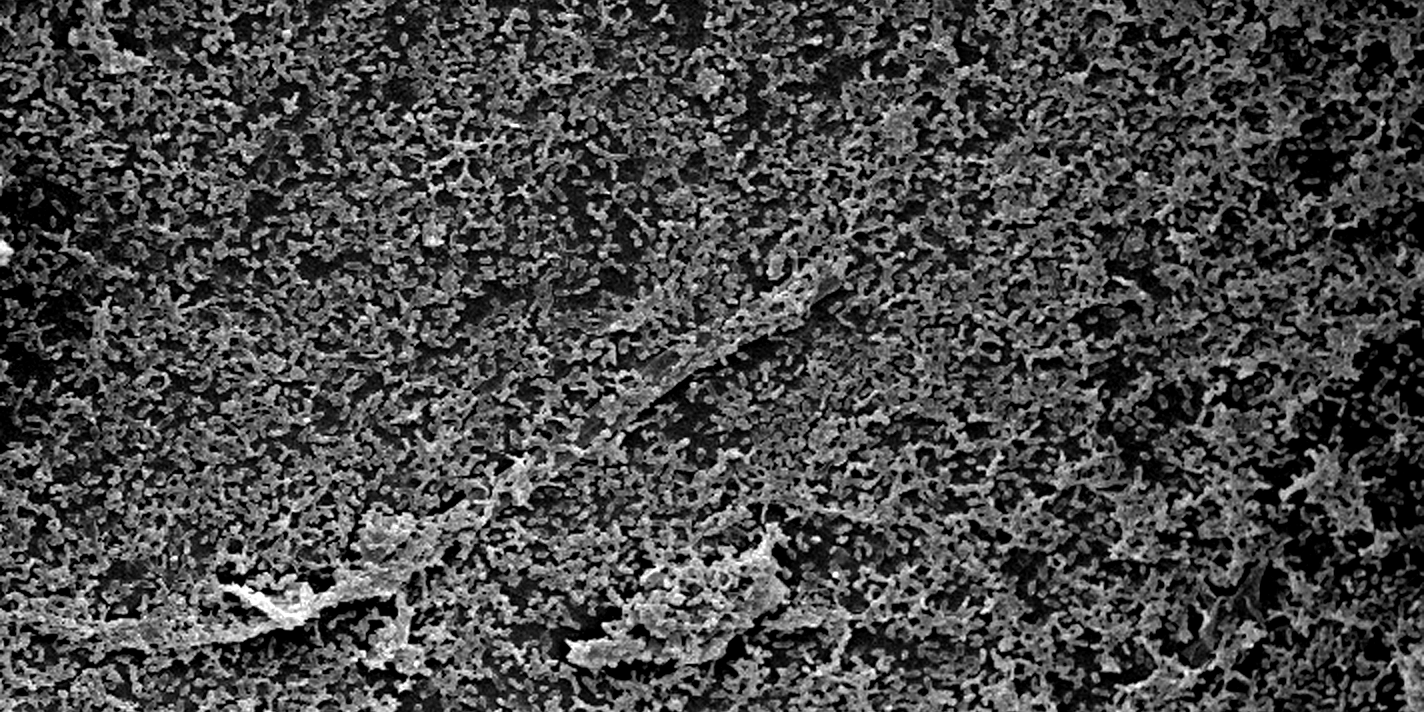

I feel like I should disclaim this article as not suitable for all audiences. If you’re squeamish, you might be grossed out, and you’ll definitely be more careful about what you touch from now on. The subject is biofilm on hard, non-porous surfaces. Biofilms are communities of microorganisms that are attached to surfaces and play a significant role in bacterial infections.

There are either four or five stages of biofilm development. First the initial attachment—free-floating microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus—a hard-to-kill bacteria that causes all types of nasty infections from skin to heart to bone. The bacteria attaches to a surface, for example a table top in a hospital room or dentist office. At this stage the cells are readily able to detach and with regular cleaning can be interrupted or removed.

In the second stage the microcolony grows on the surface and enters an irreversible attachment where the cells lay flat against the surface and resist attempts to physically dislodge them. These cells then start creating a sticky, gooey slime.

In the third stage, the biofilm is formed. Dangerous biomaterial matures into muiti-layered clusters.

Stage four—for those who claim there is a five-stage development— is a further maturation of the biofilm where the biomaterial can become antibiotic resistant.

Stage five is where the biofilm reaches critical mass and begins dispersing to colonize other surfaces. Boom! A quick, infectious spread of disease.

More bad news: bacteria that form biofilms are much more resistant to antibiotics and antimicrobial solutions. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) more than 80% of all microbial infections are biofilm related and can be hard to diagnose and treat.

What do you need to know about cleaning biofilms?

First, let’s discuss where you’re likely to find biofilms in your home or workplace. Plaque buildup on your teeth is a biofilm. Scum covering a rock in a creek or clogged pipes and drains are biofilms. The pink ring in your dirty toilet is a biofilm. Same for the pink slime in your pet’s water bowl. (Please clean your pet’s water bowl often if not daily.)

Biofilms act as the glue that holds bacteria to a surface and makes it easier for bacteria to live in a colony and therefore easier to cause of an infection. That’s why it is so important to break through and remove the biofilm during cleaning. It takes, for lack of a better term, elbow grease to cut through the biofilm. With regular cleaning you’re less likely to incur biofilm because you’re often interrupting the first phase of biofilm development (where cells can be readily detached from the surface they are attempting to cling to).

Once clean, your surface is ready for disinfecting to kill any remaining germs. Just like when you use a toothbrush to scrub the plaque from your teeth then use a mouthwash to kill the odor causing bacteria.

There are a few disinfecting processes that can actually penetrate the biofilm, killing the bacteria living there. This one-step cleaning process is very efficient. It can also be very toxic. Read the label. You’ll want to use products with a close to neutral pH and a category 4 toxicity level on the EPA chart, such as products containing stabilized chlorine dioxide or sodium chlorite. Also note the kill time which describes how fast the product kills bacteria. The faster the germ is killed by the product, the more likely you are to be successful at eradicating the germ.

Remember, regular cleaning reduces biofilm buildup.

1 Comment